The first thing to recognize about the lawsuit filed on Feb. 21 by the Michael Jackson Estate is that it was quite atypical from the get-go and has only grown more curious in the months since. But the case also could represent a harbinger of what’s to come given the rise of #metoo, the prevalence of arbitration in corporate America and the way in which federal courts are sometimes wrestling with procedure in First Amendment disputes.

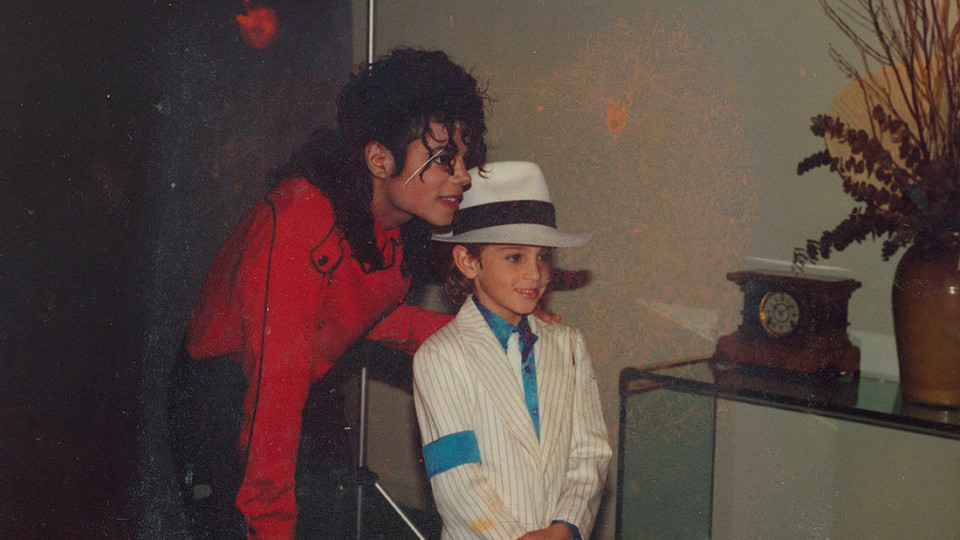

Those who run the late pop star’s business affairs believe Leaving Neverland unfairly tarnished Michael Jackson’s legacy, and to litigate the issue they are seizing upon a 1992 contract that provided the pay network with rights to air a televised concert following the release of Jackson’s album Dangerous. That more than quarter-century-old agreement also included a non-disparagement clause as well as an arbitration provision, which to borrow the assessment of HBO’s lawyer, has the potential to become “a perpetual platform to police HBO’s speech.”

When it comes to figuring out whether or not arbitration agreements govern a dispute, and whether a judge or arbitrator gets to decide jurisdiction, the Michael Jackson Estate and HBO are certainly not the first to battle over such a topic. Rather, what makes this situation particularly unique is the manner in which the Leaving Neverland case has journeyed, beginning from the way that the Michael Jackson Estate attempted to compel arbitration.

Usually when someone wants arbitration, they privately submit a demand before an alternative dispute resolution forum like JAMS or the American Arbitration Association. Resistance from the other side may mean going to court to force compliance with an arbitration agreement.

In this instance, the Michael Jackson Estate wanted to make as much noise as possible as HBO prepared to broadcast Leaving Neverland. So days before the documentary aired, a petition in public court was filed that aimed to get HBO into arbitration. But notably, the court filing became a PR weapon against the documentary. Although the Michael Jackson Estate needn’t have gone so far, the petition included substantial detail about the claims that would be brought once the two sides were engaged in arbitration. In many ways, the petition resembled the kind of complaint one sees at the beginning of a lawsuit in open court. But again, the Michael Jackson Estate really was just asking a judge to compel arbitration, not resolve whether HBO had breached the 1992 contract. To make this situation even odder, a lawyer for the Michael Jackson Estate was telling the press they wanted an arbitration “open to the public for all to see,” a wild departure from the usual hush-hush nature of what happens at JAMS.

For months, the parties explored the gateway issue of arbitrability.

Then, U.S. District Court Judge George H. Wu made his own weird move. Specifically, the judge invited briefing on the issue of whether compelling arbitration over Leaving Neverland would infringe HBO’s constitutional rights. The judge nudged HBO to file a motion to strike the Michael Jackson Estate’s petition under California’s SLAPP statute. At a July 15 hearing, Wu wondered out loud why HBO hadn’t taken his earlier wink-wink. “I was too subtle last time,” he said, “and they just didn’t appreciate the gem that was in their mine. They had the stone and they just threw it back and went on forward and kept digging.”

So taking the judge’s cue, HBO indeed moved forward with an anti-SLAPP motion.

Here’s why it matters — and has the potential of going places and becoming quite significant even beyond this dispute over Leaving Neverland.

SLAPP stands for “Strategic Lawsuit Against Public Participation.” Several dozen states throughout the country have enacted SLAPP statutes to deter people from using the courts to chill constitutionally protected speech and petitioning. After all, the sheer prospect of having to defend a lawsuit — even a frivolous one — has the potential of causing folks to censor themselves. The way in which these SLAPP statutes operate is that if a defendant can show that a claim arises from First Amendment activity on matters of public concern, then a plaintiff must demonstrate a prima facie showing of merit in the claim. If a likelihood of success can’t be established, the lawsuit hits a wall, and the defendant is entitled to recovery of legal fees.

Over the years, the use of SLAPP statutes in federal courts (as opposed to state courts) has grown more controversial because of a feeling that it alters typical federal procedure by putting the onus on plaintiffs to show a likelihood of victory at the initial stage instead of merely stating a plausible claim. As such, while some appellate circuits are now allowing SLAPP analysis in federal courts with the view that judges should apply state substantive law in diversity cases (that being, ones where plaintiffs and defendants don’t share state citizenship), other appellate circuits are coming to the conclusion that SLAPP analysis is not allowed. (See, for example, a ruling just this past week in the 5th Circuit.)

Legal observers believe that this circuit split over whether SLAPP motions should be heard in federal court is destined for the Supreme Court.

Back to the Leaving Neverland case where a federal judge is not only entertaining a SLAPP motion, but seemingly invited one. And not just over any issue but one where a defendant — HBO — is aiming to stop an arbitration. If there’s anything the Supreme Court has shown in recent years, it’s the sanctity and reach of the Federal Arbitration Act. Then again, in light of the #metoo movement, many states are leery about having tales of sexual abuse hushed up and are enacting new laws to stop certain arbitrations.

Within this context comes HBO’s argument within its SLAPP motion and the opposition filed on Thursday night by the Michael Jackson Estate.

In its brief (read here), HBO points to the “extraordinary” origins of the case — the way the Michael Jackson Estate made a “public shot across the bow, threatening to pursue and punish HBO in a ‘public’ arbitration seeking over $100 million, even before Leaving Neverland debuted on HBO.”

HBO contends this use of the court — or “speech-chilling conduct” — flouts First Amendment principles, California public policy and its due process rights. Further, HBO argues that the Michael Jackson Estate cannot establish a reasonable probability of prevailing because the 1992 agreement doesn’t pertain to Leaving Neverland, and is expired.

Again, under the second prong of the SLAPP statute, a plaintiff must demonstrate a probability of prevailing before getting a green light to move forward, but what does it mean in this situation? The immediate relief being sought by the Michael Jackson Estate is to compel arbitration. HBO seemingly argues that wherever the dispute is adjudicated, the underlying claim of breaching a non-disparagement clause is a meritless one. So will the judge actually turn to interpreting the contract at hand and the content of Leaving Neverland? It’s not particularly clear.

In the opposition memorandum (read here), the Michael Jackson Estate stresses that its petition turns exclusively “an issue of federal law under the Federal Arbitration Act” and as such, this court has no business applying California’s SLAPP law to whether or not HBO goes to arbitration. Recent Supreme Court rulings how states can’t create “procedural or substantive” obstacles to enforcement of arbitration agreements gets attention. And the Michael Jackson Estate reminds the judge of the modest chore before him.

The petition, states plaintiff, “arises out of HBO’s refusal to arbitrate. Breaching an agreement by refusing to arbitrate is not constitutionally protected activity. And even if it were, the Jackson Estate has shown a probability of success on that claim, as the Court explained in detail in its tentative order (where it definitively rejected all of HBO’s arguments against arbitration). If the Jackson Estate’s claims to be arbitrated are as frivolous as HBO would have the Court believe, it should have no reason for concern.”

In advance of a hearing on Sept. 19, days before the Emmy Awards, one last thing needs to be noted that is not in either of the briefs.

California’s SLAPP law provides an automatic right to an immediate appeal. Meaning, no matter what Wu decides, there’s a pretty good chance that the case goes up to the 9th Circuit and maybe eventually the Supreme Court before the two sides would actually settle in for the prospective “open” arbitration.

ERIQ GARDNER